There is increasing concern children are less focused in school. This is often blamed on smartphones and social media.

At the same time, there is significant pressure on schools to deliver academic results, with students’ performance on some major standarised tests dropping.

“Edtech” (education technology) companies are offering a potential solution to schools through engagement data. These data measure students’ engagement automatically and in real time.

As my new journal article explores, measuring engagement through digital programs may sound like a good idea, but we need to have a much clearer understanding of what these data are actually measuring and what kind of engagement they are promoting.

What is engagement technology?

Students in schools and universities will be familiar with “online learning platforms”. These are online spaces where learning content and resources are contained. It could be for any subject and for learning students need to do in class or at home.

“Engagement data” describes any sort of measurement on how students use these platforms (rather than results or learning). Teachers can then see their students’ data via dashboards.

Currently, engagement data are more common in tertiary education, where systems such as Moodle and Brightspace are used to deliver online content. These platforms often use a variety of metrics such as contributions to discussion forums, number of pages viewed, and assignments submitted.

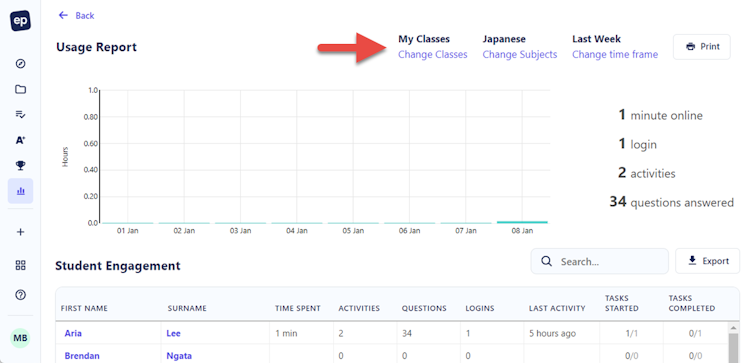

But engagement data are also finding their way into schools. For example, Education Perfect is used by more than 2,000 schools throughout Australia. It offers online learning content from Year 5 to Year 12 for a range of different subjects.

At the same time it provides analytics on students’ engagement, including the time students have spent on activities and the total number of activities they have completed. It also shows the last time a student logged in.

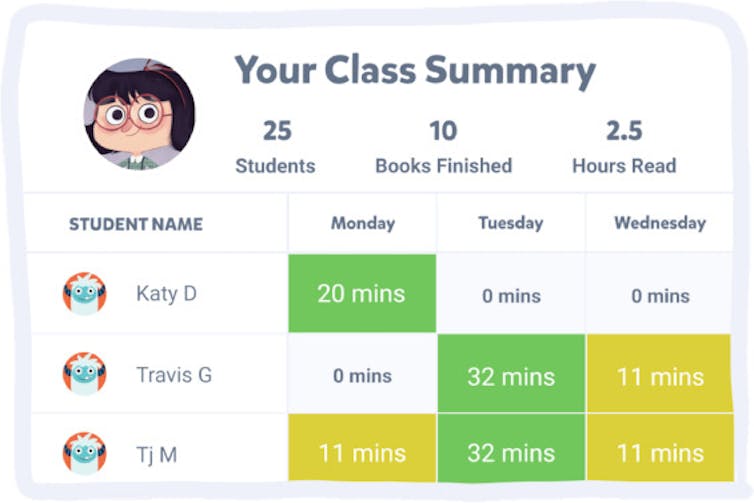

The online library app Epic is mostly used in primary schools. It keeps track of how much time students have spent reading and how many books they have “finished”.

Academic theories of engagement

Through engagement data, online learning platforms promote the idea engagement is measurable and can be expressed in numbers and graphs.

This may fit with some teachers’ understanding of engagement as students being “on task”. But it is a very limited idea compared to most academic theories of engagement used by education researchers today.

Many of these theories link engagement to feelings and attitudes towards learning, rather than just time spent doing this or that.

For example, do students feel school is actually a place where they belong? Do students feel motivated to persevere when things are difficult? Do they feel like there is a point to what they are learning?

What is engagement data measuring?

We also have to question whether engagement data are measuring what digital platforms claim to measure. Platforms may measure the time a student is logged into a specific part of the platform, but not necessarily the time a student is actually involved in a learning task.

For example, students could have a task window open and not do the task, yet the clock keeps ticking, increasing the time they apparently spent on the platform.

Task completion might be a more valid way of measuring engagement, but the mere completion of tasks is also a very narrow conception of engagement. It measures quantity of learning but not necessarily quality.

Is this data useful?

It is also not clear why teachers need information on page views and the number of times a student has logged in.

From a teacher’s perspective, it might be useful to know if a student has not been active at all on the platform. But it could be argued knowing a student has logged in on Friday evening at 9.32pm is unnecessary surveillance.

Some of these measurements are also quite common on social media platforms where companies aim to quantify user engagement. Social media giants such as Meta use metrics such as page views to calculate the value of online content, which can then be sold to advertisers.

We need to guard against viewing students simply as “users” of a product, rather than as students who need to learn and grow.

Biometric data can also be measured

While it is not a feature in Australian schools, online learning platforms may use biometic data to measure students’ engagement.

This involves using headsets or cameras to track students’ brainwaves or eye movements to see if they are paying attention. Experiments with these technologies have been conducted in Chinese schools.

While this may seem far-fetched, influential organisations such as the OECD have begun seriously considering the benefits or “promising paths” of this technology.

How are engagement data used?

We now need more research to understand the extent to which teachers and schools are using these data and why. We also need to be asking whether this is useful information to collect at all.

Anecdotally, there is some pressure on teachers to use it. While working as a high school teacher in 2021, a senior teacher advised me to show parents engagement data in parent-teacher interviews. If a parent was upset about their child’s results, showing them how little time a student was putting into their online learning seemed an easy way to rebut any criticism of my teaching, “blaming” the student for their disengagement.

However this approach avoids any discussion about the real problem. This is not the lack of time a student spends on the learning platform, but why a student is not motivated or why the lessons are not working for them.

The task of defining student engagement should be up to educators and scholars, rather than edtech companies. Just because something is easily measurable does not mean this information is valuable or necessary.

Author

Chris Zomer

Associate Research Fellow at the Centre of the Digital Child, Deakin University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article here.